REAL TALK FOR ORGANISERS

Is a BLOG series about the muddy waters of organising and social movement building. Every month we will release new articles focused on shifting organisers’ theory and practice for greater impact of their movements. Find more resources on organising and get in touch, share your ideas and feedback at comms@globalplatforms.org

I have had the privilege of training all kinds of alliances: labour unions, student groups, NGO coalitions, informal community groups. I’ve witnessed so many powerful organisers traveling the path to victory, only to be derailed by their own leadership. In these (annoyingly common) instances, members shift their focus from the target of their external enemies - a government or company, for instance - to their own group’s leaders. In such moments, movements usually hit the pause button on their goals until they can straighten out their internal mess, thus sacrificing the momentum they had built for their cause.

I have also been a member of activist groups where the aversion to hierarchical leadership is so strong that a simplistic sense of “we make decisions together” sets in, without the structure for that joint decision-making to actually flourish. Without the deliberate creation of values, group culture, and process, the members of the group with more power (say, based on gender, age or experience) invariably seize control.

Sometimes this capture of power within a group is deliberate, and sometimes it is accidental. But in all cases, it stifles the emergence of collective power.

In the words of Gee McKeown, as described in our report Sustaining Social Movements: “It always seems to be the case that there are small groups of people pulling the strings, themselves in denial that this is going on.” This culture of denial of hierarchical elements and disparities in privilege at play within the group gives way to a kind of fetishization of horizontalism. A group’s more powerful members exploit the lack of structure in the very name of inclusivity to concentrate more power around themselves.

SO HOW DO WE MAKE DECISIONS TOGETHER, DESPITE THESE INTERNAL CHALLENGES IN OUR MOVEMENTS?

Answering this question will look different for different groups, but arriving at a working solution starts with acknowledging that there are more than two types of structures. We do not have ONLY hierarchical and horizontal models. EVERY model falls somewhere in between these polls. A vertically-organised corporation, for example, may have an employee or client complaint desk to solicit feedback from stakeholders in the company. Every group and structure uses some combination of personal agency and collaborative teamwork.

Asking whether we want to form hierarchical or horizontal groups is a question likely to derail us into the tyranny of structurelessness. I have often been wrapped up in unhelpfully polarized conversations about whether the “NGO model” or “movement model” is the right structure to adopt to make change. Neither “model” tangibly exists. Each has countless sub-types. There are NGOs that are more member-led than some movements, and movements that are more authoritarian than NGOs operating under the leadership of an executive director or CEO.

The devil is in the details. We can begin to work through the nuances of our groups by asking what kinds of decisions we must make, and how we will make those kinds of decisions.

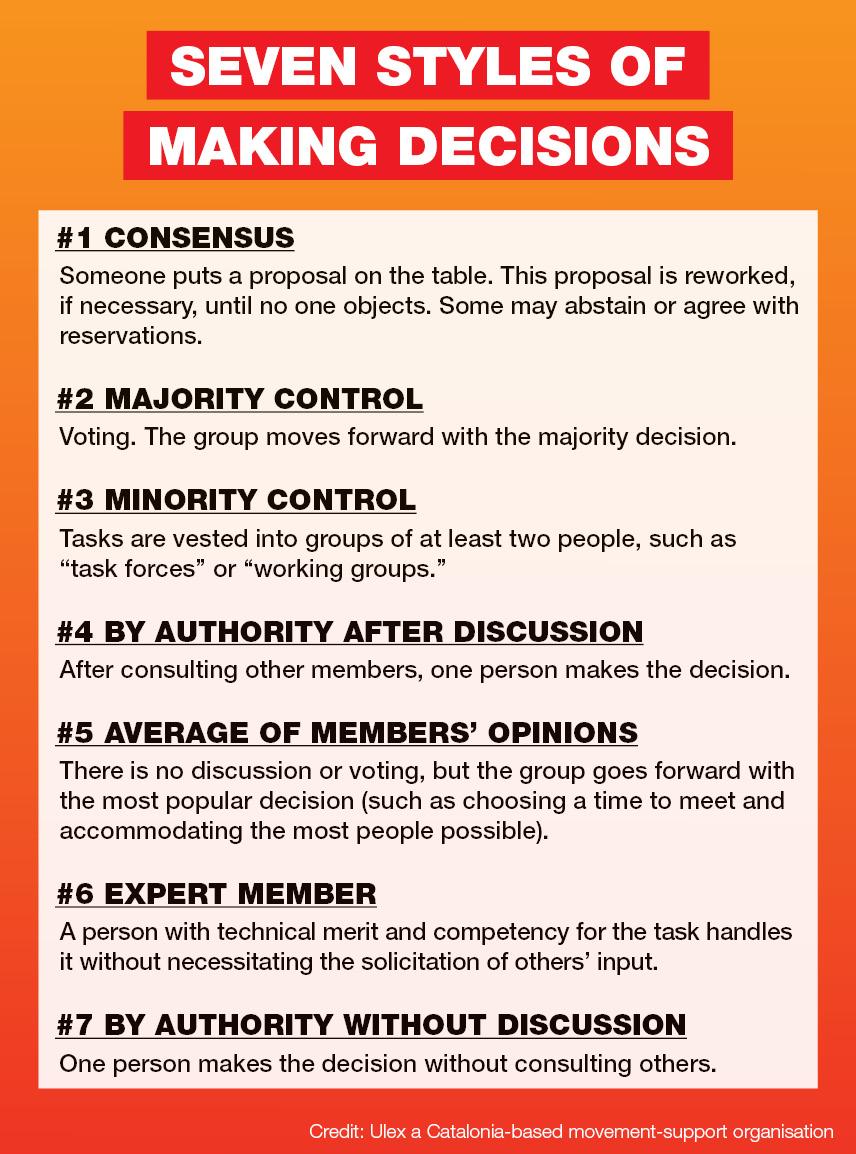

In a Club MassPower session you can watch here, Ella of the Catalonia-based movement-support organisation Ulex guided organisers through seven (non-exhaustive) styles of making decisions. In any movement or group, tasks may be decided in a number of ways, as illustrated:

Movements, organisations, banks, armies, sports teams, supermarkets: groups across diverse contexts use all or most of these approaches, often simultaneously -and not always consciously. Movements have the burden of creating MORE structure - not less - to deliberately empower decision making in ways that are strategic, expeditious, inclusive, and scalable, based on their objectives and circumstances.

To use an extreme illustration, if your movement is organising a protest where police brutality is anticipated, it is unlikely that protesters will stop in the middle of their action to build consensus on whether and how to treat an injured member. Rather, that power might be vested in an expert with a medical degree or a working group that has gone through first responder training.

An executive director of an NGO might find it wise not to accept a grant by her own authority without discussion, but rather consult staff before making the decision, or perhaps solicit their green light and programmatic amendments through a consensus process.

To achieve their goals, groups must develop nuanced decision-making systems and cultures. There is no one-size-fits-all horizontalism. Sharing power through processes deliberately built for the group’s objectives and context will increase the group’s chances of success.