The following interview with organizer, activist, and author Dan Glass follows our previous interview with Dr. Stella Nyanzi on similar topics. His insights offer something to learn both for queer and LGBTQIA+ movements and movements engaged on other issues.

This interview is the second in a series of interviews with anti-colonial activists throughout the commonwealth — a colonial geopolitical community that has been gravely affected by tragic laws, norms, and violences imposed upon people who do not fall neatly under heteronormative and cisgender identities, genders, and sexualities.

Q: Why did you write United Queerdom, and why did you go back to the 'writing cave' again to write Queer Footprints?

Dan: A few reasons. The first is, whenever I get annoyed with the amount of work, I just remind myself that it’s nothing compared to the work of the incredible, exceptional people who fought tooth and nail for queer people and people living with HIV and AIDS, who have been essentially murdered by the British establishment and who have committed their lives to remember the dead and fight for the living.

Spending a year and a half writing — it’s nothing compared to the people who have spent the better part of their lives fighting for accountability, justice, and continuing freedom for hundreds of years. The British empire is responsible for the majority of homophobic persecution across the world, since Henry VIII introduced the Buggery Act of 1533?, which has been transported as one of the British empire’s most successful exports of homophobic legislation. Sixty one countries across the world, many of them in the Commonwealth, have homophobic legislation, and so much of that is because of the British empire. This is why it’s so important to say “partial decriminalization.” People who are persecuted in their countries are attempting to flee and are dying in the Mediterranean, or are locked up in detention centers and treated like crap in the UK because of the hostile environment.

In 2021 we celebrated 50 years of radical pride in Britain, but obviously this is a key reminder of the gravity of the work still to do. The original foundation of gay pride was absolute freedom for all.

I always talk about homophobia and HIV-phobia simultaneously because that’s my direct experience. Where there is homophobic legislation, there will be higher rates of HIV across the world. I’m an activist with the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP). Despite the seemingly bleak responses I’m giving, I really f***ing enjoy this work. When I started with the research mapping and interviews and articles, I had like forty maps of London and two thousand case studies that have contributed to our freedom today. Because of institutional homophobia in the form of both decriminalization and legal cases like Section 28 which wasn’t overturned until 2003, we never got to know about all these incredible people and situations. So the [research and writing] is really illuminating and insightful. It’s almost like we’ve had culture amnesia, intergenerational amnesia, because we’ve not been allowed to find all this out. I really enjoy it, to the extent that I don’t want to do anything else.

I’ve really stripped back social life because when I’m writing, I can’t do much else, because I’m in the zone. I’m also not a lot of fun because all I want to talk about is the book! I’ve had a few situations where I’m like, “I have to leave this party, because I’m not making sense to anyone.”

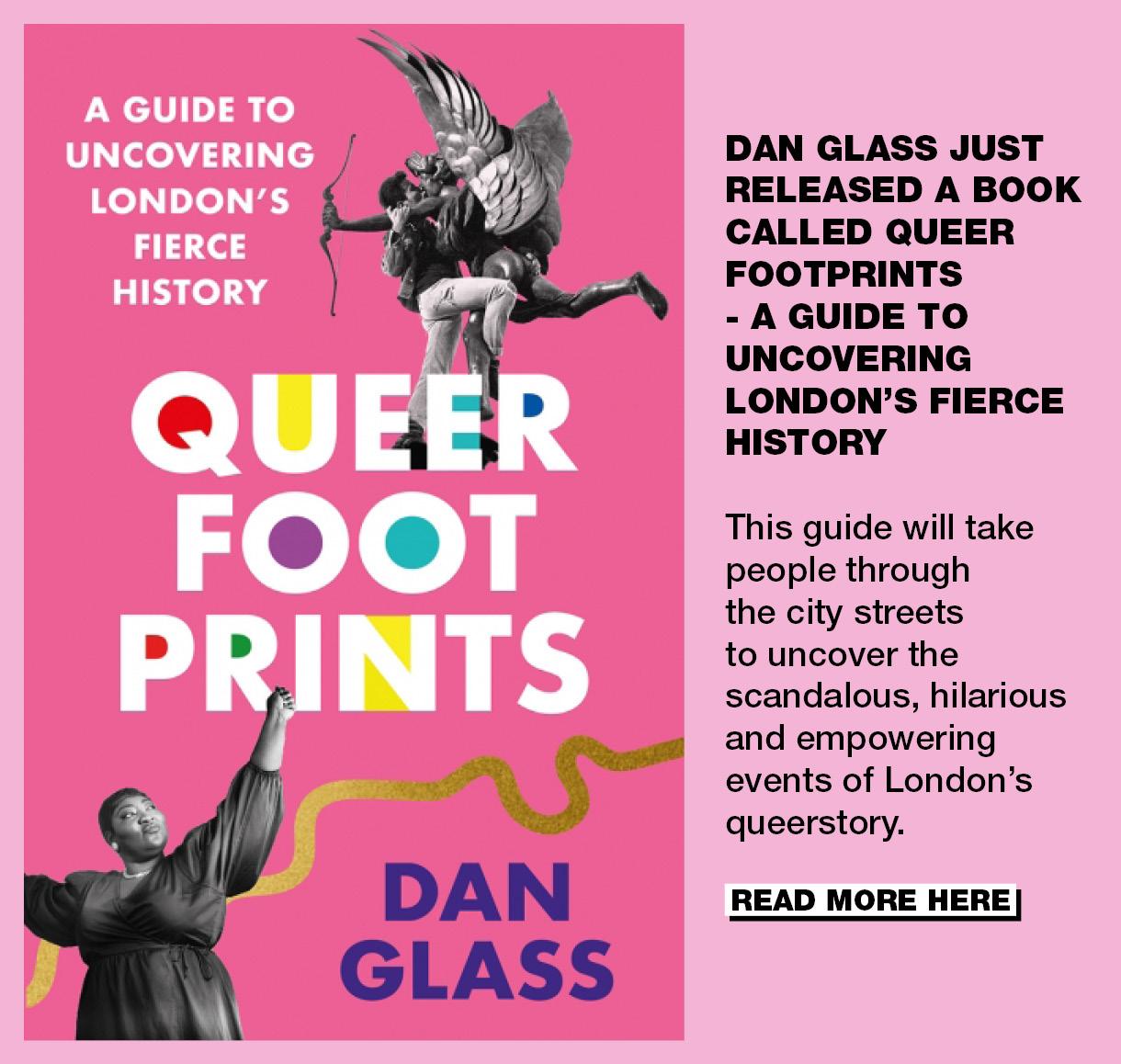

With Queer Footprints: A Guide to Uncovering London’s Fierce History, now I have twelve chapters — twelve little queer babies. This is brought down from forty chapters, so I’ve done way too much research. [Having also published United Queerdom], hopefully it’ll become a trilogy. But that’s the beauty of it: realizing that the more you know, the more you realize you don’t know.

Obviously there’s connections between [these books]. United Queerdom was written around interviews with the founders of the Gay Liberation Front and lots of personal stories. With this one, it’s a different kind of book. It’s none of my own shit. People say that in making your first book or your first album, you have to get a lot of your own shit out so that you can look at the bigger picture. Now that this is out of my system, I’m glad that I can now look at all the wider, incredible movements.

This new book [Queer Footprints] is an immersive walking guide of London. When it comes out, there will be outcry from groups across the neighborhoods of London, barely touching the surface.

Q: Why did you write United Queerdom, and why did you go back to the cave again to write Queer Footprints?

Obviously you can read it at home, but I’m encouraging everyone to read it out in the streets. Our very presence is building queer community in itself. As the Gay Liberation Front said, “Out of the closet and into the streets!” I’m making it very accessible — wheelchair friendly, with toilets and benches along the routes, and beautiful maps to illustrate it. I want this book less on the queer history shelves and more on the touring shelves and the education shelves. I’m trying to write it so it gets out of echo chambers.

Q: Once on a London layover, I took a donations-only tour. Will you also have your own guides next time I’m in London?

So this is why I’m moving back to London next year. I’ve been speaking with queer groups in London, dedicating next year to do tours, including with those I’ve written about — in Soho, Trafalgar Square, Brixton. I’ve mainly focused on living history so that those I’ve written about are largely still with us.

Doing queer tours of London is my favorite job I’ve ever had. It’s deeply empowering because you’re taking over the streets and raising consciousness. It also offers a global perspective. Some tourists from Kampala once asked where our local queer center is to go for a little visit after, and at the time we did not have one. Even though in Kampala, there is much more tyrannical legislation, there are actually many more queer spaces. One tourist from Russia offered their own perspectives, also directly influenced by British Section 28.

Q: I appreciate that you’re not just a historian isolated in a room, but you want this real-world, present-day connection that sort of organically works its way into organizing, into understanding and learning from each other. You know how often we feel segmented as authors, researchers, historians, writers, artists — often perceived as removed, as elitist. How do such people connect with the struggle happening now?

Arundhati Roy talks about the connection between writing and activism. She says writing is activism. Your words affect the establishment. Don’t get me wrong: I’m gagging to get back to the trenches of grassroots direct action. I’m not "a writer by trade,” but I am an activist. I’ve taken the time out to do this writing, but I’m itching to get back to Beautiful Trouble styles of activism and training.

What we’re facing in the UK with new bills and increasing authoritarianism and the crackdown of protests, I cannot f***ing wait. The whole point is that we must understand our history to deliver on what our ancestors started out: absolute freedom for all. Books are also really empowering for those who cannot get to the street and practice direct action. Even writing a zine of “know your rights” is writing. It is empowering people to take direct action.

The Bender Defenders network was born in response to rising LGBTQIA+ hate crimes. We had a demo last February called Queer Night Pride because a lot of the attacks were happening at night. Now we’ve got forty new people each week coming to self-defense and boxing training classes. It’s so brilliant because it’s deeply empowering at a physiological level and psychological level. It’s fun and it’s funny. Our patron saints are characters from East Enders.

Right now our LGBT elders often need to go back into the closet when they go to so-called care homes, due to the homophobic abuse in these homes. So there are legends who started Pride who have to go back into the closet.

Q: We have disparate efforts — why is it important to unite for shared politics and goals? There is a co-optation of unity itself, which your first book addresses: Pride co-opted by capital, by tech bro start-ups that want to look presentable in an age of identity politics. Tell me your definition of queerdom. Why unite it?

The Anonymous Manifesto first distributed by the Pride Festival in New York has said, “Using ‘queer’ is a reminder of how we are perceived by the rest of the world. It’s a way of reminding ourselves that we don’t need to be charming people who keep our lives discrete and marginalized in a straight world… Queer can be a rough word, but it is also a sly and ironic weapon we use… to use against [homophobes].”

For me queer is way beyond sexuality and who we chose to sleep with. It’s about anyone who refuses to be pigeonholed and thinks outside the box. It’s beyond binaries. It’s beyond reductiveness and narrow-mindedness. Queer is transcending any stereotypes of how we should exist in the world. It’s different from gay, because it’s all-encompassing in the spirit of “none of us are free until we all are.” We have to overcompensate for the demographics that are less free.

Queer is a big “f**k you” to narrow-minded, hierarchical, dominator culture. Why unite it? Because, unfortunately, (as Paulo Freire describes the consciousness of the oppressed), some of the most racist things I’ve ever heard have come out of the mouths of queer people. We must look at things at an intersectional level. Oppressed communities can unfortunately step into the shoes of the oppressor. This is when the trauma turns in on ourselves and our communities. We are in this together, which means we share a common battleground of dominator culture. That’s why this new book highlights, for instance, Brixton’s fame for the unity between the feminist, anti-racist, and queer community. We have all faced police oppression.

Q: What do you think movements can learn from queer organizing, especially movements that don’t center LGBT+ issues, rights, or membership? Is there anything queer organizing teaches better than organizing traditions of any other movement?

Theatrics are one of the biggest skills we offer. The tattoo on my arm, for instance, is attributed to a Gay Liberation Front action against a 1971 Festival of Light. To get into the [religious, homophobic, right-wing, anti-abortion] festival, the Gay Liberation Front dressed up as nuns and were welcomed in. They planned a theatrical action where, when the pastor said “let there be light,” they descended down to the stage, did the can-can, and released mice on the stage and shut the whole festival down.

We have an incredible history of wit, satire, self-deprecation. All this is a survival mechanism as well. Police don’t know how to deal with these approaches. They help secure winning actions.

We’ve got a lot to teach from a trauma-based, abolitionist perspective, as well. We have been deeply targeted by the military industrial complex, and still are. There’s a lot to teach regarding trauma, survival, and healing.

Queer organizers also have a lot to teach about global solidarity. Stonewall in 1969 was deeply connected to the women’s liberation movement, the Black Panthers, and others around the world. At the 1970 Black Panther convening, Huey Newton made the infamous speech that it is time to be in solidarity, and that homosexuals might in fact be the most revolutionary. Two activists present at this speech returned home to the UK to start the Gay Liberation Front. The gay movement was a trade unionist movement, a housing movement, an anti-police movement. It was many things. Ripples across the world from these movements contributed to anti-war movements. We now have a united goal of global decriminalization.

Q: Tell me about what you’ve learned from your solidarity efforts with the Global South.

I’ve learned to always, always, always distrust the bullocks that comes out of BBC programs. On one program, it covered “the worst places in the world to be gay,” and Uganda was number one. When I went to Kampala, a lot of my friends there said, “Actually, I think it’s the best place in the world to be gay.” Britain thrives on homonationalism and the idea of “backwards black countries.” F*** you; you started the problem in the first place. You’re perpetuating neocolonialist sentiment.

True, Uganda has homophobic legislation and lots of things going on, but this cannot invisiblize the wonderful queer activism going on. I’ve learned to challenge neocolonialist perspectives.

Trans-led projects have also taught me that queer people are challenging the assumptions that “if you make it to the West, all will be glitter and rainbows.” This isn’t true. There are homophobic attacks, detention centers, refugee camps. We need to dig where we stand, deepen our roots. Challenge stereotypes, challenge the savior-complex.

I’ve become keenly aware that I have little time for NGO and charity projects. They are often part of the saviour complex. Roy talks of the NGOization of resistance. This speaks to our solidarity with Uganda, with Russia, with Poland. We’ve got a lot of unlearning to do in places where homophobic infrastructure is directly inspired by the British.

Q: What do you think Gen Z queer organizers can learn from those who came before them? Is there anything they can teach their movement elders?

Heartstopper is a visionary program about what life should be like. People talk on social media about binge-watching Heartstopper and I’m like, “Are you kidding me? I’ve got to stop every five minutes and have a break.” I have to make time to reflect on life without Section 28.

We always need a balance of past, present, and future when it comes to transformational change. One practical example: facilitating intergenerational movements requires listening. Deep active listening. The elders in the GLF fought for just the terminology of “gay.” I remember a lot of the younger activists thought that GLF elders were being transphobic, missing the correct pronouns and so on. I was like, “Wait, they are not being transphobic; they’re just from a different era where they had to just fight for ‘gay,’ which for them encompassed the spectrum. They’re also old and some have dementia. But they have even held me to account and are sharp as f***ing nails.”

The older generation has so much to learn from the younger generation about new forms of organizing, sharpness in messaging, digital activism. One of the most beautiful things to come out of intergenerational organizing is these lifelong friendships. People are struggling for each other’s care and wellbeing.

Q: We have many elders who took a lot of hits for us. We continue to benefit from their discipline and focus and tenacity. There is a rising cancel culture that tends to overlook and under-appreciate the imperfect-yet-important gains that were made, in favor of performative culture.

I’ve got zero time for cancel culture. It’s the right-wing’s wet dream. The fascists wank on it. They love our cancel culture. Activism is a lifelong transformation. We have to allow each other to f*** up.

Q: The right wing is incredible at consolidating its power between the center and the far right. Our inability to work between center-left and radical anarchism is really disappointing. Although debate over how to get the utopia we want and how to build it is important, we don’t seem to be very good at consolidating ourselves.

By age 30 or 25, you should be able to say in two sentences what your purpose on the planet is, what your political strategy and goals are. There’s been such an attack on spaces and movements by the right wing. They have effectively demolished transformative movements. Environmentally, racially, socially — systematic inequality in general — they are winning because they have attacked our transformative spaces.

Of course I’m romanticizing, but if we look at the black power, trans liberation, and queer liberation movements from the 70s and 80s, there was an explicit framework and mission statement of what we need to do to achieve our goals. The more clarity we have individually and collectively within our movements — the sooner, the better.

Our movements can be flexible, but we need to be able to say, “I am a socialist, and this is how I commit my life to working towards that. Or, I’m an anarchist-feminist, and here’s my strategy for that.”

If you’re not part of a physical community, you’re easily going to be cherry-picked by the establishment. You can easily be bought off.

Q: Tell us one hope and one fear you have for the future of queer organizing. What would be the measure ten years from now that your books have made an impact?

My hope is inspired by Maya Angelou. She says that the epitome of love, at its deepest, most unconditional and transformative, is serenity. It’s not joy or connection; it’s peace — a form of soul-activism. I just want a deep sense of calmness. I hope all queer activists of every age in every place have a deep peace.

One fear I have is that we don’t connect struggles and that we don’t challenge the environmental injustice that is going on. None of us — queer or otherwise — can enjoy the planet if we don’t stop its exploitation. My other fear is that we will stop protesting and just get lost on the internet. Nothing is more effective than taking to the streets.

What I’m trying to encourage with the new book Queer Footprints, is to use it as a tool for individual and collective empowerment, but also I’m encouraging people to buy a copy to chuck through the windows of homophobic establishments — or a copy for someone who may not have access to a queer community.

I want the books to be a tool for individual and collective empowerment, but also a physical tool to stop business as usual, as well as spiritual awareness. That’s my tiny little ask for these books’ future.

This sounds cheesy as f***, but if there’s one person who reads it and thinks “I’m not an idiot for feeling like this” and feels a bit more of a human connection, and hopefully is dissuaded from hurting themselves (much as I felt as a kid) — even just one person who feels less alone and isolated — then that’s a win for me.