When the state targets and imprisons artists, it attempts to remove from the ranks of society those who are listening, watching, who sense injustice and possess creativity in speaking truth to power. A dangerous thing.

In February 2021 the Myanmar military staged a coup and began a brutal crackdown on anyone and everyone who stood in their way; a total of 2,500 pro-democracy activists and civilians have been killed by military crackdowns on the pro-democracy movement. Within weeks critical sections of the Law Protecting the Privacy and Security of Citizens were suspended, and amendments were made to the Penal Code, the Code of Criminal Procedure and Electronic Transactions Law, among others, expanding offenses, creating new ones and enabling warrantless surveillance, search and seizure, arbitrary detentions and executions. As of 19th December 2022, a total of 13,088 people – including artists are in detention, and 139 have been sentenced to death (and 4 executed) (source: AAAP).

ANONYMOUS POET: In 2016, a court in Myanmar sentenced Anonymous Poet to six months in prison under charges of defamation for writing a satirical poem about then President Thein Sein. Following his release, he co-founded an activist organisation promoting freedom of expression in Myanmar, and now leads a resistance group.

Q: Where did your interest in poetry come from?

I am from the middle part of Burma, so I arrived in Yangon when I was in middle school. At school I read books including poetry. In Burmese culture if you are interested or have a crush on someone you have to give them love letters, so I started writing love poems for girls that I liked, that’s how it started. Over the years I became more interested in poetry. At first it was only about love, but later the more that I read, the more I found the suffering of the public, failures of the system and injustices happening in this country. Poetry brought me into politics. Before I was advocating about peace and anti-war movements and the more I saw injustice the more I brought these issues into my poems. I wrote a poem about a violent crackdown on protestors, where a women farmer was shot in the head, about the 2015 student revolution, I wrote about what I saw happening all around me.

Q: You were imprisoned in 2016 – what impact did your experience have on your poetry and activism?

I was charged for two things (Article 66(D) under the 2013 Telecommunications Law, and the other was 505(B) for state defamation). I got arrested and charged by the court, but I stayed in prison while I was awaiting sentencing, so by the time the NLD government came into power they withdrew 505(B) from my case, I was left with 66(D) and the court sentenced me to 6 months, which I had already served. The government owes me 1 month of prison time served. In other countries they would have to pay you for these things, but in mine we must thank them for releasing me. It was a turning point for me going to prison. There was not much to do other than to think, read books and write poems. When I got out, I started to think, when you get out of prison you get more publicity, and this is a chance to speak more loudly. That’s one thing. Another is that before I went to prison, I was all over the place joining different movements and causes, but after prison, I realized it’s not efficient to be everywhere. I am a poet and I write poems, so I asked myself what can I do for human rights? I started to work on freedom of speech and literature and media and the more I worked on this the more I became passionate about it.

Q: How did you write while in prison?

During my term I had to stay alone in my cell, so I wrote alone and mostly about injustice, oppression, home sickness (and missing my girlfriend). You can’t write or share this kind of stuff in prison, it's not allowed, so you must write it privately. You can’t bring it [poems] to court when you get to see people attending your hearings, I had to hide it in my underwear and when I got there, to give it to them quickly so that my poems could reach the outside. I read around 200 books in prison. I read and read and read.

Q: Since 2021 you have been leading a resistance group.. What impact has this role had on your poetry, and vice versa?

I write less now, not as much as I used to. I published a book for revolutionary support, it was an e-book of poems I wrote. A lot of my poems reflect what I’m experiencing now, it’s different than before, more about my resistance journey. I’ve been writing for a long time and people know me, so it’s easy to talk with others through my poetry and reading and writing. It makes it easier to lead, to communicate and advocate with young people.

Q: What has been the role and impact of art in the resistance?

Mostly they [poets] are very empathetic people and feel what other people feel, and not just based on your own reality and experience but also the experiences of others. Art plays a big role. Revolution itself is an art. How you create this art beautifully is how you can win this revolution. Art plays a very crucial role in this revolution in Myanmar. Also, when you talk about things, it doesn’t really sound deep, but if you create it into a poem or art form, it becomes deeper, clearer, and it communicates a better understanding to people. That’s how you can use art to advocate people, to inspire them, motivate them. In resistance, you must lead, inspire, and motivate people, not just fight all the time. That’s where art comes in, to connect us, support each other. I also think that art can also be a tool or a weapon. The poems especially, are all about how you feel it, a good poem can make you feel happy, or sad, or even depressed. You can definitely use a poem to send a message.

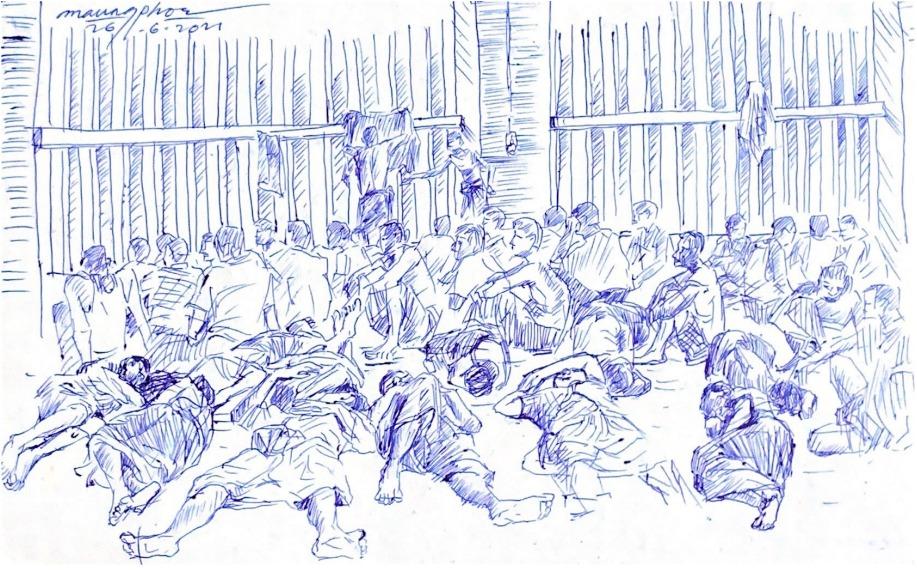

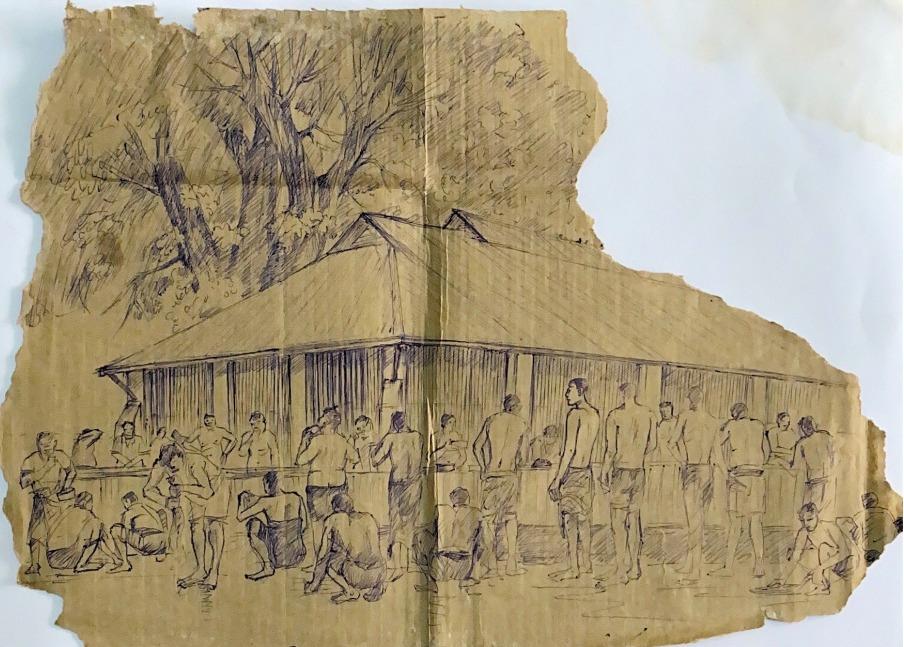

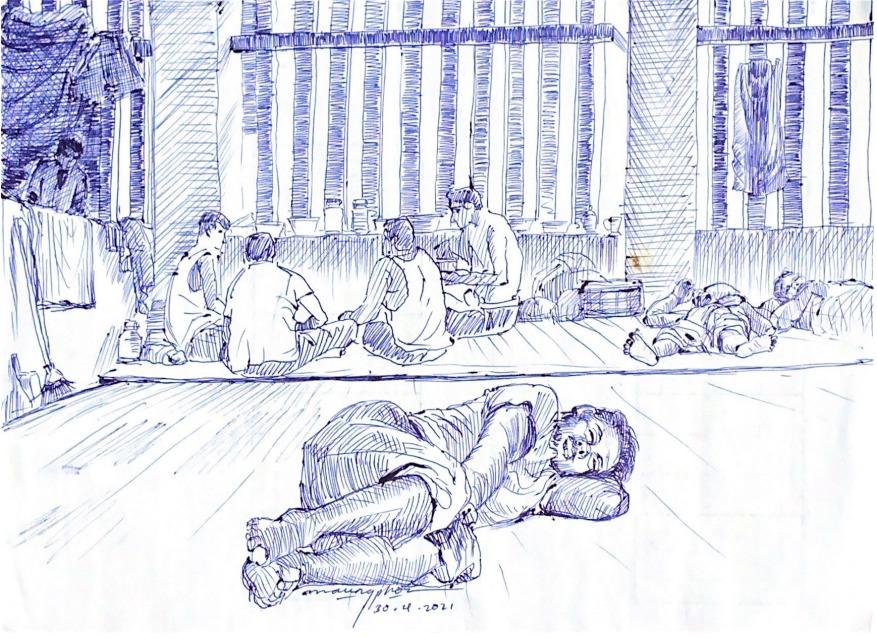

MAUNG PHOE (alias): Artist Maung Poe was arrested in 2021, along with his wife and son (who were released shortly afterwards) for possessing protest-related materials in their household.

Q: You were imprisoned recently – what happened?

I was drawing pictures of General Min Aung Hlaing shooting himself in the streets, in different townships, I drew three big ones, the eyes alone were 3ft. While I was doing it, I was wearing a mask to protect my anonymity. They [police] were looking for who did them but couldn’t get to me. There was an officer in my neighborhood though, and what happened is that a young person who protested (also from our neighborhood) was shot in the head, and that officer brought the cops to the neighborhood to the family of the protester. At the time I was angry and got into an argument with the officer. Two weeks later he brought police officers to my house for a ‘check’. In Myanmar we have to submit a ‘guest list’ to quarter officers to keep track of who lives in what household. I had a lot of revolutionary posters and books related to the revolution, they saw that, took it as evidence and arrested me. So, I was arrested, but not actually for the main work that I did, just because of what I had in the house. They arrested me under Section 505(a) and charged me with this. I spent 6 months in prison, but before the sentencing, there was a release of some prisoners, and I was one of them.

Q: What was your experience of creating the drawings at Insein prison?

Before the coup, people were coming to me for portraits. I'd do it and they’d pay me. It was more like a business. My first night in prison there were 470 people in a room for 150 people. It was so sweaty, so hot. We had to sit very tightly and close to each other. I thought “this is crazy. I need to record this. I need to draw this”. If you want to go to the toilet you have to ask the officer, which I did 4 times that night just so I can be permitted to stand up and look around. I wanted to look around the room and take mental images for drawing later. After 10 days I moved to a different cell with 130 people and more space.

One day during lunch, I saw someone who was drawing on paper with a pen. I had to make friends with him and ask him to spare drawing materials for me. That’s how I started. At first, I was drawing portraits of fellow prisoners. I would save paper and cut it into smaller pieces, I’d save anything I could find. I drew portraits of everyone in my room, 130 people. Also, portraits from other cells. During break times I was allowed to go outside, and people would approach me to draw a portrait of them. I would agree to everyone, I drew almost 200 portraits, among them there are also prison officers. I drew portraits of officers and sometimes their family members. If they were higher in rank, they would just call me over and tell me to draw. With lower ranking ones, I could chat with them and learn about their stories too, their thoughts about the current situation, and in exchange they would also give me pens and paper for my work.

After I’d finished drawing, I would give it to them. Some prisoners kept them, some would bribe officers to turn them into soft copies and send them to their families. They were getting their portraits out to their families in their own ways. Behind each drawing I would write my details and tell them to keep it and send it to me later when they get out of prison. Now that I’m out I’ve gotten in touch with 50 others who are also out, and they have sent me soft copies.

Q: What has been the role and impact of art in the resistance?

Before I was very laid back, not really putting myself out there in the art scene. In prison I was motivated to, and felt like a responsibility to do more, because I had the skill and had to document what was happening. I could not be lazy about it. I am so proud and grateful for that experience, of being able to draw. It has been a breakthrough for me, I respect myself more and am more grateful for my ability. In prison, I spent time with another 5 painters, they were very supportive, it was a community inside prison. I was drawing for a lot of people; it created a sense of unity and solidarity in these drawings. Any form of art, music, painting, drawing, any kind of art, can really support and lift people and unite them for change. I really felt this from my own experience. When I drew the large images in the streets, it was unplanned, myself and a friend bought supplies and started painting, I had never drawn such large-scale work so didn’t even know how much paint I needed, it ran out halfway, and when it did, I didn’t even need to go buy more because the people around me brought me what I needed. They really supported me in the process of painting it. A lot of people came out on the balconies, clapping, motivating me to continue.

Q: What would you like to share with other artists, activists like yourself?

I am grateful to be here and sharing my stories and work. What we have been facing during this coup is the worst and most despicable experience, an unjust situation. Any human who experiences this will stand up and say we can’t accept it. Anyone will use whatever they have to share their voice (not just me, not just artists, poets, musicians but anyone). We are on the way to creating a society which is equal and free but until we get there we must go through a lot, there may be more situations like this out there waiting for us, but it’s our responsibility to stand up and fight to create a society that is fair, free, equal and with respect for one another.

Denied of rights, privacy and control, for the artists in detention and the communities fighting injustice, art and creativity remain a source of strength and power. The creative force unleashed by resistance to the coup in Myanmar has served to chronicle what is happening, to inspire and motivate and to continue the fight.